This semester–and yes, my life at mmbty-some years of age is still measured in semesters–has been the longest and the slowest that I can remember in some time. I am fairly certain that the trip that I was supposed to have made to London in early February was either:

- made in a different lifetime

- made in an alternate universe

- made by someone else who stole my identity for that trip and I now need to track the bugger down and get my life back.

In short, that jaunt to London was a flash of a visit, the delight and point of which has been pulled to the depths of my memory by the riptide of this semester’s duties. (That moment of verbal melodrama provided courtesy of an utterly shattered brain.)

Despite the complete void in my memory, my camera has photos on it that suggest that I did somehow make it to the good old Victoria & Albert during that blip, and pictures don’t lie. Well, my pictures don’t lie because I haven’t got the foggiest how to doctor them. I could probably sit them down on the sofa and mess with their minds, but properly doctor ’em? Nope.

Anyway, my camera tells me that (true to form) I spent a fair bit o’ time in the medieval rooms, and it appears that I was thinking about home furnishings and accessorizing. I suppose, there’s nothing like a tin-can of a hotel room to make you think about a spacious home. The tin-can I remember. Oh, and I believe there was a very happy interlude with a scone in the V&A cafe…. It all comes back eventually.

Ivory book covers. This year’s must have for that special person in your life who has everything… except a conscience.

Always make sure that when guests enter your house, they know where they stand: on your turf. Tile that foyer with your coat of arms as did John of Gaunt.

The arms of John of Gaunt and his wife Constance, 1372-89. Clear, coloured and flashed glass with paint. (from the collection of Horace Walpole, 1717-77)

Looking for a new backsplash? Tile is so passé. Consider using Limoges plaques. Nothing says “money to burn” like gilded copper with champlevé enamel. Anxious about looking excessive? Go for a spiritual theme like the resurrection to subtly suggest your mind is on higher things. Besides, don’t we all feel like this when the dishes are done?

Plaque with the Resurrection of the Dead, circa 1250. Limoges, France.

Have a hankering to decorate with a touch of the outré? Did you watch that scene with the clutching hand in Harry Potter and think to yourself, “Well, maybe if it weren’t so poorly manicured that would work on the Green Room’s mantle….” Then, for that soupçon of je ne sais quoi (ou pourquoi), try a reliquary. Let the neighbors show off their aquamanile collection. Nothing says, “I’ll see your lousy bronze lion water pot and raise you an even more priceless objet d’art!” like a reliquary. (Nearly all body parts represented in current market. Some disassembly may be required.)

Now empty reliquary from 1250-1300, Southern Netherlands.

Personally, I have to confess that I would collect aquamaniles in a heartbeat. So far as my shallow little heart is concerned, they beat reliquaries hands down. But then, I’ve never been into the outré and as for soupçons, I’m more a soupspoon girl. Speaking of which….

This baby from c. 1430 was clearly intended for display and not use. Netherlands, silver enamel, gilding and niello (black composition).

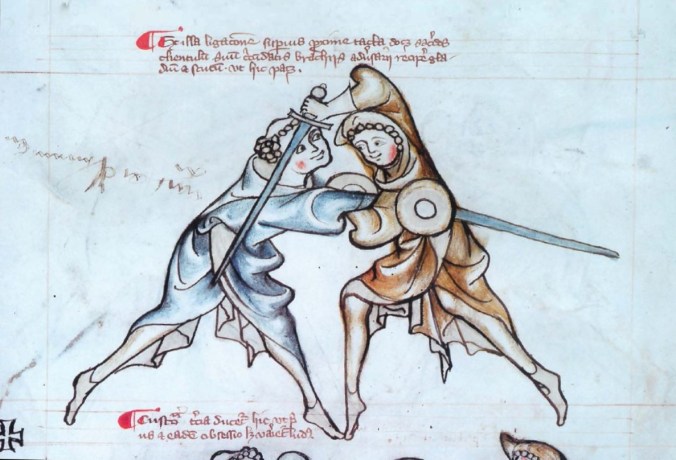

Have bare walls? Well, why not set off this year’s trendy, dark green walls with a set of ivory love scenes produced in Paris between 1300-1325? Aim the proper lighting toward them and they’ll not only frame themselves, but they’ll also set the tone. We recommend scenes like these which are straight out of romance literature. Did we mention tone?

Lastly, a little personal accessorizing is always necessary. Why should one’s house be better appointed than oneself? (It shouldn’t.) I like my accessories with a touch (a soupçon even) of humor. Case in point: this molded leather number which is equal parts Dean Martin and the Prioress from The Canterbury Tales. Who could ask for anything amore?

Moulded Italian leather bag, 15th century.

Well, I could. Of course, I could. The aquamanile collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for starters….

At least, so I am told by the variety of people who feel an uncontrollable urge to comment upon it. Countless are the times that I have been told that my writing is illegible. It’s not illegible. It’s small. Alright. Fine! It’s tiny, but tiny ≠ illegible. This purported illegibility has been hammered home both gently (and un-) by everyone from examiners in grad school to my own sweet kith and kin. Adding insult to injury (FYI hammering hurts), my writing been compared to everything from Sanskrit to the tracks of panicked field mice. For my part, I do not consider it unreasonable to expect people to have magnifying glasses on hand. Preparation is half the battle in life.

At least, so I am told by the variety of people who feel an uncontrollable urge to comment upon it. Countless are the times that I have been told that my writing is illegible. It’s not illegible. It’s small. Alright. Fine! It’s tiny, but tiny ≠ illegible. This purported illegibility has been hammered home both gently (and un-) by everyone from examiners in grad school to my own sweet kith and kin. Adding insult to injury (FYI hammering hurts), my writing been compared to everything from Sanskrit to the tracks of panicked field mice. For my part, I do not consider it unreasonable to expect people to have magnifying glasses on hand. Preparation is half the battle in life.

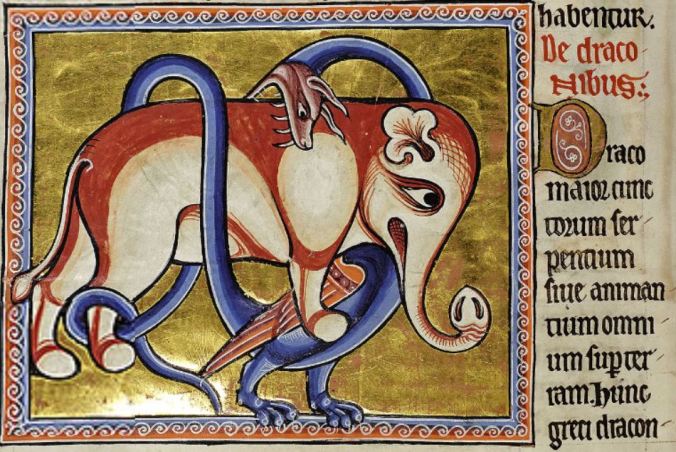

Francesco Stabili, the composer of the Liber’s “encyclopedic [vernacular] poem dealing with the natural sciences, physics and religious philosophy” burnt at the stake (Imaginary Creatures, p 32). My money is on the dragon portrayed here hunting him down and crisping him for writing a poem that inspired such a spectacularly unflattering and spotty portrait.

Francesco Stabili, the composer of the Liber’s “encyclopedic [vernacular] poem dealing with the natural sciences, physics and religious philosophy” burnt at the stake (Imaginary Creatures, p 32). My money is on the dragon portrayed here hunting him down and crisping him for writing a poem that inspired such a spectacularly unflattering and spotty portrait.