When I was in graduate school at University of Toronto, Trinity College’s annual Friends of the Library book sale was an event well worth the price of admission, and by admission I mean the nominal fee one had to pay to get in early on the first day. Some years were better than others depending on what one was hunting for. If the right person was downsizing their library, it was pure gold. One year, I nabbed both a volume I of the English Historical Documents (Whitelock) and the two-volume Shorter Oxford English Dictionary and the Shorter Cambridge Medieval Histories and and early edition of Stenton’s Anglo-Saxon England. No matter what the year, the EETS (Early English Text Society) volumes on offer never seemed to be what I needed, and I was not in a position to say, “Good Lord, a mere $30 for Richard Rolle’s Fire of Love? But of course!” It’s hard to justify building up one’s library of Middle English devotional literature if that is not one’s focus.

Much as I love used books, it is not unheard of for them to make my thoughts drift to hellfire and damnation. I once loaned a copy I had of a textbook to a student whom I knew to be in a tough financial spot. “Return it to me at the end of the semester,” I said, never imagining that I needed to include some gentle admonition that the use of vivid pink highlighter in someone else’s books was not the done thing. Who uses highlighter on someone else’s book, let alone their professor’s?! When the book was returned ruined and without apology, I consigned the textbook to the dumpster and the student to Terrace 2 of Purgatory with the indolent and unshriven. Then, there was the student to whom I loaned Frank Barlow’s wonderful book on the Godwins and that little wretch never returned it! I love Barlow. I love the Godwins. I loved that damn book. It’s a very, very, very good thing I could not remember to which student I loaned it because s/he would have been consigned (vengefully and immoderately) to the seventh ring of nether hell with the thieves. Admittedly those were my books, but the latter was “used” when the student decided to keep it and the former was most definitely used (and abused) when I got it back.

I am not a fan of errant ink in books neither my own nor other people’s. That is not to say that I am adverse to writing in books. The margins of my books are littered (a word that probably captures the true value of my comments and observations) with comments in pencil—fine, tiny pencil—that can be erased should I regret, or think better of a comment. The one exception to my “no ink” rule is in inscriptions. I love finding a used book with an interesting name and place and, if I’m lucky, date. Something about that little trio turns the proverbial tables. It is no longer the book coming into my possession, but rather that I am entering into the book’s history much as when one meets a new friend who naturally has a life that preexists your acquaintance. Something about that attendant past stays with me as I read, and I sometimes feel I enter a sort of conversation with a book’s past owners.

So, on the odd occasions when I pick up the ancient volume of Longfellow I inherited from my parents, I read with one “Mr. H. H. Kennedy” who clearly wrote with a dip pen and whose rather 19th-century style of handwriting suggests that he may have purchased the book for the $1.00 it cost when it was printed in 1882. Longfellow, I must admit, it not generally my tipple. I’m much more likely to spend an hour imbibing from one of the two volumes I have of Michael Drayton’s poetry, in which pursuit, “ROGERS” keeps me company. While there is no “Mr.” on the page to certify this assumption, there is something indefinably masculine about the confident surname smack dab in the center of the front page. Towards the bottom, city and date place the self-possessed Rogers in New York, February 1, 1954. I like to think of him sitting in Bryant Part to read Drayton after he’s spent a lovely morning in the Morgan Library & Museum studying Assyrian seals.

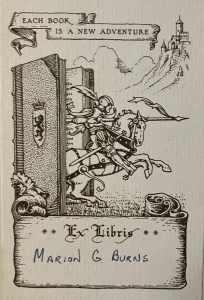

It is perhaps only right that a trilogy of saga-esque novels would have a more complicated history than volumes of poetry. My three volumes of Sigrid Undset’s Kristen Lavransdatter (Knopf 1946) each have two facing book plates from each of their previous owners. “EACH BOOK IS A NEW ADVENTURE” proclaims one bookplate which bears a picture of a knight charging out from the covers of a book. The bottom of the bookplate reads, “Ex Libris Marion G. Burns”. If the style of this first bookplate suggests a young reader, the handwriting does not. Marion wrote her name in clean, simply written large and small capitals. (I like the way she does her ‘A’.) It has style without being self-conscious. I think I would have liked Marion. The bookplate on the facing front page contains a picture of a ruinous Greek temple on a seaside cliff. “Mildred Knowles” in a handwriting with rather swooping (but not round) capitals. Under her name, Mildred conscientiously wrote “from Kathy – Christmas 1986”. Something about the second bookplate that makes me think that it is only Marion who reads with me; only Marion who thought deeply about Kristin’s life and experiences, and whose heart was wrung as mine is by these tales. I do not feel the same about Mildred. There’s just something about the self-consciousness of the bookplate of hers that niggles at me. Indeed, I wonder (without any justification whatsoever) if she even read the books. I likely do her a great injustice and have probably earned myself time in…. Oh, what ring do slanderers go to? Is it Purgatory or the Inferno? Bother.

If the style of this first bookplate suggests a young reader, the handwriting does not. Marion wrote her name in clean, simply written large and small capitals. (I like the way she does her ‘A’.) It has style without being self-conscious. I think I would have liked Marion. The bookplate on the facing front page contains a picture of a ruinous Greek temple on a seaside cliff. “Mildred Knowles” in a handwriting with rather swooping (but not round) capitals. Under her name, Mildred conscientiously wrote “from Kathy – Christmas 1986”. Something about the second bookplate that makes me think that it is only Marion who reads with me; only Marion who thought deeply about Kristin’s life and experiences, and whose heart was wrung as mine is by these tales. I do not feel the same about Mildred. There’s just something about the self-consciousness of the bookplate of hers that niggles at me. Indeed, I wonder (without any justification whatsoever) if she even read the books. I likely do her a great injustice and have probably earned myself time in…. Oh, what ring do slanderers go to? Is it Purgatory or the Inferno? Bother.

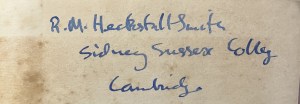

More recently, I plunged over the metaphysical cliff in the wake of John Donne. My purchase of Metaphysical Lyrics & Poems of the Seventeenth Century: Donne to Butler (Oxford, 1952) came with a inscription in silvery blue ink: “R. M. Heckstall-Smith Sidney Sussex College Cambridge”. It actually took me a little while to make sense of the signature, but when I finally did, I kept thinking, “That name looks really quite familiar.” And so, while I do not usually google the names of my books’ previous owners, I did on this occasion. Now, when I pick up this book, I cannot help but smile at the thought of a young, undergraduate version of Dick Heckstall-Smith reading metaphysical poetry with me. Perhaps the young jazz saxophonist only bought the book for a course, but I like to think it was more than that. I like to think that he picked up our book every now and then over the years of an innovative career. Perhaps some poem by Vaughn or Donne provided a spark that required some musical expression from him. There’s no way of knowing, of course, but it’s lovely to think of the book spinning out worlds beyond itself and the words on the page shedding denotation and slipping into unbounded music.

And so, while I do not usually google the names of my books’ previous owners, I did on this occasion. Now, when I pick up this book, I cannot help but smile at the thought of a young, undergraduate version of Dick Heckstall-Smith reading metaphysical poetry with me. Perhaps the young jazz saxophonist only bought the book for a course, but I like to think it was more than that. I like to think that he picked up our book every now and then over the years of an innovative career. Perhaps some poem by Vaughn or Donne provided a spark that required some musical expression from him. There’s no way of knowing, of course, but it’s lovely to think of the book spinning out worlds beyond itself and the words on the page shedding denotation and slipping into unbounded music.

Some times, the OED selects words that I’ve never seen before and never, ever, ever want to forget. Here, for example, is one of my favorites from some time back:

Some times, the OED selects words that I’ve never seen before and never, ever, ever want to forget. Here, for example, is one of my favorites from some time back:

The other day as we were strolling through the magnificent passages of the medieval Nasrid palace of the Alhambra, one of my sisters said that if felt like time traveling to walk through the passages. It was like being thrown into the stories we had read as children. I understood what she meant. When strolling through a medina in Meknes several years ago, I stood and watched a storyteller weave his magic around the gathered crowd. Between the sounds, smells, responses of the crowd, the whole brought to life the opening of one of my favorite childhood stories, Eleanor Hoffman’s Mischief in Fez. It was a pleasant sort of illusion–equal parts personal nostalgia and fairy tale.

The other day as we were strolling through the magnificent passages of the medieval Nasrid palace of the Alhambra, one of my sisters said that if felt like time traveling to walk through the passages. It was like being thrown into the stories we had read as children. I understood what she meant. When strolling through a medina in Meknes several years ago, I stood and watched a storyteller weave his magic around the gathered crowd. Between the sounds, smells, responses of the crowd, the whole brought to life the opening of one of my favorite childhood stories, Eleanor Hoffman’s Mischief in Fez. It was a pleasant sort of illusion–equal parts personal nostalgia and fairy tale. If it’s true that the ceiling in that Hall was made to symbolize the seven heavens, then the placement of the throne in this room makes child’s play of the whole “divine right of kings.” For this reason, I suppose the echoes of death and power my sisters’ heard were perhaps more true than the echoes of poetry I liked to imagine in the gardens. The past of fortresses and fortifications is more truly grounded in blood and bone than anything else. If you want a sobering read of the history of the Alhambra, keep going with the aforementioned history by Irwin. It washes away some of that sepia patina of fairy tale pretty quickly.

If it’s true that the ceiling in that Hall was made to symbolize the seven heavens, then the placement of the throne in this room makes child’s play of the whole “divine right of kings.” For this reason, I suppose the echoes of death and power my sisters’ heard were perhaps more true than the echoes of poetry I liked to imagine in the gardens. The past of fortresses and fortifications is more truly grounded in blood and bone than anything else. If you want a sobering read of the history of the Alhambra, keep going with the aforementioned history by Irwin. It washes away some of that sepia patina of fairy tale pretty quickly.

All straight? Good. This is more important knowledge than you can imagine.

All straight? Good. This is more important knowledge than you can imagine.