I am not, I know, the only person to have vexed relationship with her GPS. Being sent to major highways for the “fastest route” when a local byway really would be more efficient is a ubiquitous GPS violation. Recently, however, my mobile’s GPS has started pranking me, sending me off unnecessary exits, and even changing the destination. Imagine Hansel and Gretel’s bag o’ crumbs starts laughing at them, “MWAH HAH HAH!” and snaking towards the wicked witch’s house. That’s my GPS.

Last week, on one of the few and excruciating occasions when I had to drive into Boston, a traffic snafu sent me digging around with one hand for the mobile, trying to get in the damn password, and speak in my destination, all the while dutifully swearing at and being sworn at by other drivers.[1] Within a few miles of hitting “GO,” my voice joined the choir of anguished souls screaming into the ether.

“Wait! NO! NO! NO! NO! NO! Not Rutherford Circle! Holy Saint Æthelthryth, how did I get here? How do I get out? Stupid GPS! I’m gonna diiiiiieeeeee!”

I leave the expletives to my readers’ rich and fertile imaginations.

Thus, I expect that it has always been, in sæcula sæculorum. Just as we curse the GPS on our mobiles, countless navigators over countless ages have undoubtedly cursed out cartographers or compass-makers.[2] Imagine the poor Viking who’d made holiday plans for Turks and Caicos only to find himself staring at the rocky coast of Newfoundland. [Please, read the following in a voice that is equal parts Yosemite Sam and the Swedish Chef.]

“If I ever get my hands on Cnut Redthumb, I’m gonna rip that laggard limb from limb! I knew I should have bought the map off of Harald Bluetooth.”

Of course, it goes without saying that anyone dumb enough to buy a map from Cnut Redthumb only has himself to blame: everyone who was anyone in medieval seafaring knew better than to trust Redthumb’s maps. [3]

When it comes to medieval maps, it is not so much a matter of all maps not being created equal, so much as maps being created for different purposes, which is not so different from maps today. I, for example, love caves and the maps thereof, like the map of Wind Cave National Park (Fig. 1) which adorns the wall by my desk. However usefully and beautifully it displays the multiple and intersecting layers of the cave system, were one to attempt navigating the surrounding upper world with it, one would roundly deserve to be trampled by any of the massive bison which inhabit that park. I am a firm believer in stupidity being its own reward.

Many of the maps that populated the cartographic landscape of the middle ages require the adjustment of expectation. Where we have topographic maps and the like to help us better understand our physical geography, medievals had schematic alternatives like T-O maps which laid out their religious geography (see Fig. 2). When readers encountered maps where the waters of the Mediterranean, Nile, and Tanis formed a ‘T’ separating other parts of the known world like Africa, Asia, and Europe, they knew where they stood, so to speak. (It may help to notice in reading this map that East is uppermost.)

Figure 2. St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 236, p. 89 – Isidorus, Etymologiarum liber XI- XX. 92nd century

http://www.e-codices.ch/en/csg/0236/89/0/Sequence-420

So, readers of Isidore’s Etymologiæ who came upon this map of the lands of Noah’s sons after the flood would never have dreamt of navigating physically with such a map. That wasn’t its point. Like all good T-O’s it provided readers with a rough schema of how the world they knew of related to the world of scripture and the history therein.

Where T-O maps are pretty sparse, other medieval maps present the world, or sections of it, in far more detail. Fig. 3 is by one of my favorite medieval English artists, the thirteenth-century Benedictine monk, Matthew Paris. I will sing Paris’ praises in another post. They deserve to be sung. For now, consider his map.

Figure 3. Matthew Paris’ Map of the British Isles. Cotton MS Claudius D. vi. f. 12 v. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=cotton_ms_claudius_d_vi!1_f012r

With its strongly delineated rivers and abundant cities, Paris’ map shows England as a beehive of development. Sure, you couldn’t find your way from A to B with it, but this map tells you that the journey would be worth it because there’s a lot to see at both points. Looking at this map, the rivers seem to pulse like veins through the heart of England, which, I suppose, is both truth and fancy. And I defy anyone not to be smitten by the way that Cornwall (or Cornubia in Latin) is trying to make a break for it across the Celtic Sea.

A contrasting English map (though not a map of England) shows just how different maps can. The Cotton Map (Fig. 4), was drawn in the eleventh century, some two hundred years before Paris drew up his. Like its more schematic T-O cousins, the Cotton map is oriented with the East on the top. The maker of the Cotton map provides more detail about what is important in the different parts of the world. If it’s not as generally accurate as Paris’ map, we can say that everything stays respectably within the borders. (If you’re looking for the British Isles, they’re in the bottom left.)

Figure 4. “Cotton Map,” BL, Cotton MS Tiberius, BV f.56v http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/magnificentmaps/2014/03/good-news-for-fans-of-medieval-maps.html?_ga=2.27813624.578205670.1531822193-858079620.1522788273)

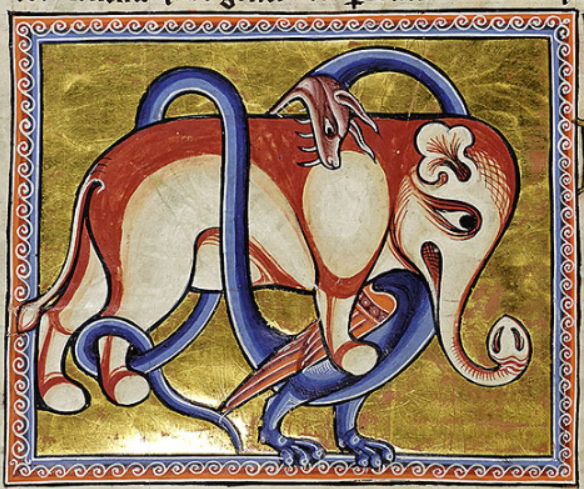

Throughout the Middle Ages, there are a variety of world maps such as the Cotton Map. On them, we find the traces of the delight medievals took in parts far-flung, in wild stories, and in the mythic histories of the wider world.

I’ll come back to those wild and wider stories in the next post with the mother of all mappæ mundi (maps of the world): the Hereford Cathedral Mappa Mundi. Where Cotton map’s is home to one solitary lion in the East, the Hereford is chock full of beasts natural and un-.

[1] In Boston, swearing is cosmologically as well as existentially necessary. If a Bostonian drives without swearing, it actually messes with the space-time continuum.

[2] We’ll completely leave out word-of-mouth directions like “Second star to the right and straight on ‘til morning.” I mean, what the dickens kind of directions are those? Forget the fact that “right” is relative based upon which way one faces. Forget, moreover, the fact that the stars dance around, so that second star to the right is going to be different in December than it is in July. Morning?! Are we talking break of day? Full dawn or perhaps full-on morning? This is the kind of directional negligence lawsuits are made of.

[3] This is a gross lie. I leave it to my readers whether the gross lie is a) the slander of Cnut; b) the existence of Cnut; c) the idea that any self-respecting Viking would content himself with talk of laggards and limb ripping; or d) all of the above.

A wider-ranging and decidedly less idiosyncratic take on medieval maps can be found on the British Library’s Maps and Views blog.

It had made a little fire for itself to heat a kettle of water, and while the girl saw scones laid out, there was no grape jelly to be seen, so that her hopes of sensible conversation rose at once.

It had made a little fire for itself to heat a kettle of water, and while the girl saw scones laid out, there was no grape jelly to be seen, so that her hopes of sensible conversation rose at once.

Alas, no such luck. Closer inspection reveals it’s a cat cleaning itself. That is a sight which, frankly, never bears closer inspection. It beats me why the illuminator decided that the cat should clean itself while lounging on bellows. I could make up a story about bagpipes playing in the background as the illuminator worked and something about subconscious thoughts of squeezed cats, but I know I have at least one reader of Scottish descent who resents slighting references to bagpipes. So, I’ll leave that little mystery where it is and step away, simply commending the CBL to those of you planning a trip to Dublin.

Alas, no such luck. Closer inspection reveals it’s a cat cleaning itself. That is a sight which, frankly, never bears closer inspection. It beats me why the illuminator decided that the cat should clean itself while lounging on bellows. I could make up a story about bagpipes playing in the background as the illuminator worked and something about subconscious thoughts of squeezed cats, but I know I have at least one reader of Scottish descent who resents slighting references to bagpipes. So, I’ll leave that little mystery where it is and step away, simply commending the CBL to those of you planning a trip to Dublin. The ramshackle creature returned the girl’s stare with all the insolence of a haystack roused suddenly (and improbably) to life. Very slowly, the beast tilted its head to one side as if sizing the observer up. Something about the deliberateness of the movement made the girl revise her original impression of the creature as “rather cute.”

The ramshackle creature returned the girl’s stare with all the insolence of a haystack roused suddenly (and improbably) to life. Very slowly, the beast tilted its head to one side as if sizing the observer up. Something about the deliberateness of the movement made the girl revise her original impression of the creature as “rather cute.”