Prefatory Apology: To my friend who works in cartography. You know who you are. You know, moreover, who I am and that there is no help for me. Mea culpa for what follows.[1]

Well, after the last two or three deeply earnest posts, I have wholly exhausted my shallow reserves of solemnity, and will now return to my modus operandi of chronic irreverence, quotidian frivolity, and ubiquitous piffle. I think I want that last on my tombstone: L.R. Smith, purveyor of ubiquitous piffle.

It’s not even 7 a.m. and that’s the epitaph done. Methinks I’m in for a ripsnortingly productive day.

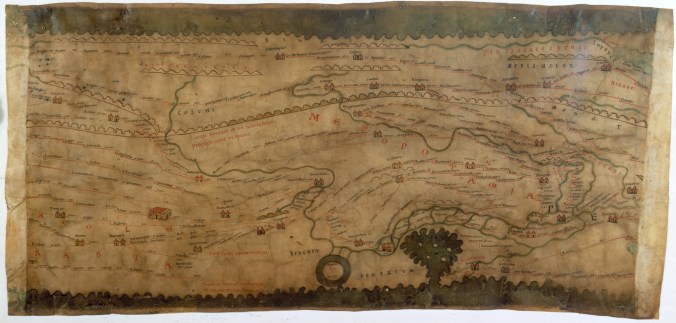

Speaking of ripsnorters, one of the maps that I never got around to discussing was an absolute monster of a map. Although itself made in the Renaissance, the Peutinger was based upon a much earlier map which had served as a model for medieval mappæ mundi, or maps of the world. And what a world the Peutinger Map represents. It is essentially a road map of ancient Rome from the house of Pretorium Agrippinae in the upper left across eleven glued folia to”PIRATE” in the lower right of the last folio. It is both delightful in its beauty and impressive in its scope and implication.

If you go to the viewer here, you can scan through and get a sense of what a monster of a map it is. Excerpts like Figure 1, which shows the Mesopotamian Valley with its winding rivers and scattered cities, simply cannot do it justice.

Figure 1. excerpt Peutinger Map. Hosted by Ancient World Mapping Center at UNC, Chapel Hill.

Thematic maps like the Peutinger with its road and cities contain hundreds of stories that are lost upon us unless we either know or take the time to hunt down the correct volume of Loeb and do due diligence matching up history with cartography. I’m going to save you the trip to the library with a gem, or perhaps cheese-curd, of forgotten history.

If one scrolls over the map toward the coast of North Africa, one finds Numidia (approximately where modern Algeria is today). This was the site of De Bello Iugurthino (The Jugurthine War) which took place between 111–105 BC when Jugurtha of Numidia took on Rome. We know of the story from Sallust (or Gaius Sallustius Crispus, born about 86 BC) who his version of the events sometime after 41 BC.

Figure 2. Numidia

For those who don’t know, the Jugurthine War (Yogurt War) was the great dairy war of the Roman Empire. This was a trade war to caste the current U.S. president’s trade wars with various international economies (or personalities) into deepest shade. Really great. Tremendous even. Think back to the 2015-16 battles over milk pricing and quotas in the EU–because who among us didn’t follow that exercise bureaucratic folly with bated breath–then just let everything go really, really sour.

On the one side, there were the Romans who were promoting their new technology of bacteria and fermentation (Team Yogurt). On the other side, there were the Numidians who wanted to preserve their well-refined traditions of souring and coagulation (Team Curd) without some big bureaucratic power dictating processes or products. Since the Numidians were dealing with the Roman Empire which employed the most cutting-edge methods for international arbitration, the results were predictably messy. Essentially, the only folks that came out of this well were the early adopters of lactose intolerance who played Switzerland and stayed out of the whole mess.

Alright, this is a complete and utter fabrication. I feel the need to confess what is probably blindingly obvious because I once unwittingly misled a very earnest Harvard graduate student with a yarn about the private papers of the famous Bollandist Hippolyte Delehaye. Poor lamb. (The graduate student, that is. Delehaye could hold his own.) Perhaps I should have started by introducing myself as L.R. Smith, purveyor of ubiquitous piffle.

A word to the curious or earnest:

If you really want to follow up and read the story, you can find it in Loeb vol. 116. With the exception of the Classicists among you, I don’t think you’ll find Sallust’s history isn’t nearly as interesting as mine.

To read more about the Peutinger:

- Richard J. A. Talbert’s Rome’s World: The Peutinger Map Reconsidered , Cambridge UP, 2010.

- Simon Hornblower, Anthony Spawforth, Esther Eidinow, Eds. The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization, 2nd Ed. Oxford UP, 2014 See pp. 490-491.

Alas, no such luck. Closer inspection reveals it’s a cat cleaning itself. That is a sight which, frankly, never bears closer inspection. It beats me why the illuminator decided that the cat should clean itself while lounging on bellows. I could make up a story about bagpipes playing in the background as the illuminator worked and something about subconscious thoughts of squeezed cats, but I know I have at least one reader of Scottish descent who resents slighting references to bagpipes. So, I’ll leave that little mystery where it is and step away, simply commending the CBL to those of you planning a trip to Dublin.

Alas, no such luck. Closer inspection reveals it’s a cat cleaning itself. That is a sight which, frankly, never bears closer inspection. It beats me why the illuminator decided that the cat should clean itself while lounging on bellows. I could make up a story about bagpipes playing in the background as the illuminator worked and something about subconscious thoughts of squeezed cats, but I know I have at least one reader of Scottish descent who resents slighting references to bagpipes. So, I’ll leave that little mystery where it is and step away, simply commending the CBL to those of you planning a trip to Dublin.