All babies come to that developmental stage wherein they begin popping, gurgling, and shushing to themselves as they explore the joys of vocalising. Eventually they find their way to words and often to their particular words of choice (‘no’ being favorite for obvious reasons). Sometimes children love particular words not for their meaning or anything to do with communication whatsoever, but simply for the wonderful feel of the word when spoken. I remember as a child loving words with ‘er’ sounds in them like ‘worm’ and ‘burp’, the latter much to my oh-so-proper mother’s consternation.

Words in which sense and sound coalesce are, to my thinking, particularly satisfying. I’m not referring here to onomatopoeia but something more substantive as in words like ‘exasperation’, ‘blandish’, ‘eluctation’, ‘glorious’, ‘plight’, ‘treacherous’, and even the humble ‘worm’ that I so adored as a child. Indeed, some of the very words used to phonetically identify sounds do themselves aurally convey their meaning. ‘Plosive’, ‘fricative’, and ‘sibilant’ with their respective puffing, friction, and hissing all sound like what they denote.

The word ‘exasperation‘ (from the Latin ex-asperō, to make quite rough) provides a perfect example of this mingling of sound and sense for the whole word is one continuous in- and exhalation of long-suffering. Where that first blot of syllable smacks one in the face, that second vowel feels like the in-drawn breath as if one is slowly, deliberately counting to ten. This, when followed by that sibilant /s/, is the very sound of someone at their wit’s end, the syllabic equivalent of “God give me patience!” The [ex]plosive /p/ that follows indicates that no divine gift of endurance has been forthcoming and it’s all going pear-shaped. The /ʃ/ with which the final sigh of a syllable begins expels the breath in one last plea for the grace to suffer fools before one clenches one’s teeth on the word’s end. It’s over. You know it, and in a very few seconds, those fools by whom you are beset will find out how very, very over it is.

Forget flash fiction. Words like ‘exasperation’ are dramas all by themselves. They just need to be given life and breath.

These days, rather than repeating words like ‘worm’ and ‘burp’ to myself ad infinitum for the pleasure of how they feel and sound, I suppose I treat words more like wine, savoring them for how they play upon the senses, for their colour, sound, and even scent. For the sake of savoring, I share one of my favorite Michael Drayton sonnets to be read aloud (since poetry is always best so). The bolded words are those in which sound and sense coalesce evocatively for me. While I know that others may find other words more or less evocative, I cannot imagine any reader not being intoxicated by the final six lines.

Truce, gentle love, a parly now I crave,

Me thinkes ’tis long since first these warres begun,

Nor thou, nor I, the better yet can have:

Bad is the match, where neither partie wonne.

I offer free conditions of faire peace,

My heart for hostage that it shall remaine,

Discharge our forces, here let malice cease,

So for my pledge thou give me pledge againe.

Or if no thing but death will serve thy turne,

Still thirsting for subversion of my state;

Doe what thou canst, raze, massacre, and burne;

Let the world see the utmost of thy hate:

I send defiance, since if overthrowne,

Though vanquishing, the conquest is mine owne.

N.B. For any who might say this is no more than phonesthetics (sound symbolism), I would say no. I’m not claiming any instrinsic meaning to any of the consonant clusters much less the phonemes above. Rather, I’m attending to the breath and movement of the word as a whole word. Of course, I willingly confess I don’t really understand the whole phonesthematic business. So, if there’s someone out there deeply devoted to that theory, I would be happy to hear more, but let’s agree to make delight and revelry rather than prim pedantry the point.

Drayton, Michael. “Sonnet 33 (63)”, Poems of Michael Drayton vol. 1, ed. John Buxton. Harvard UP, 1953, 18.

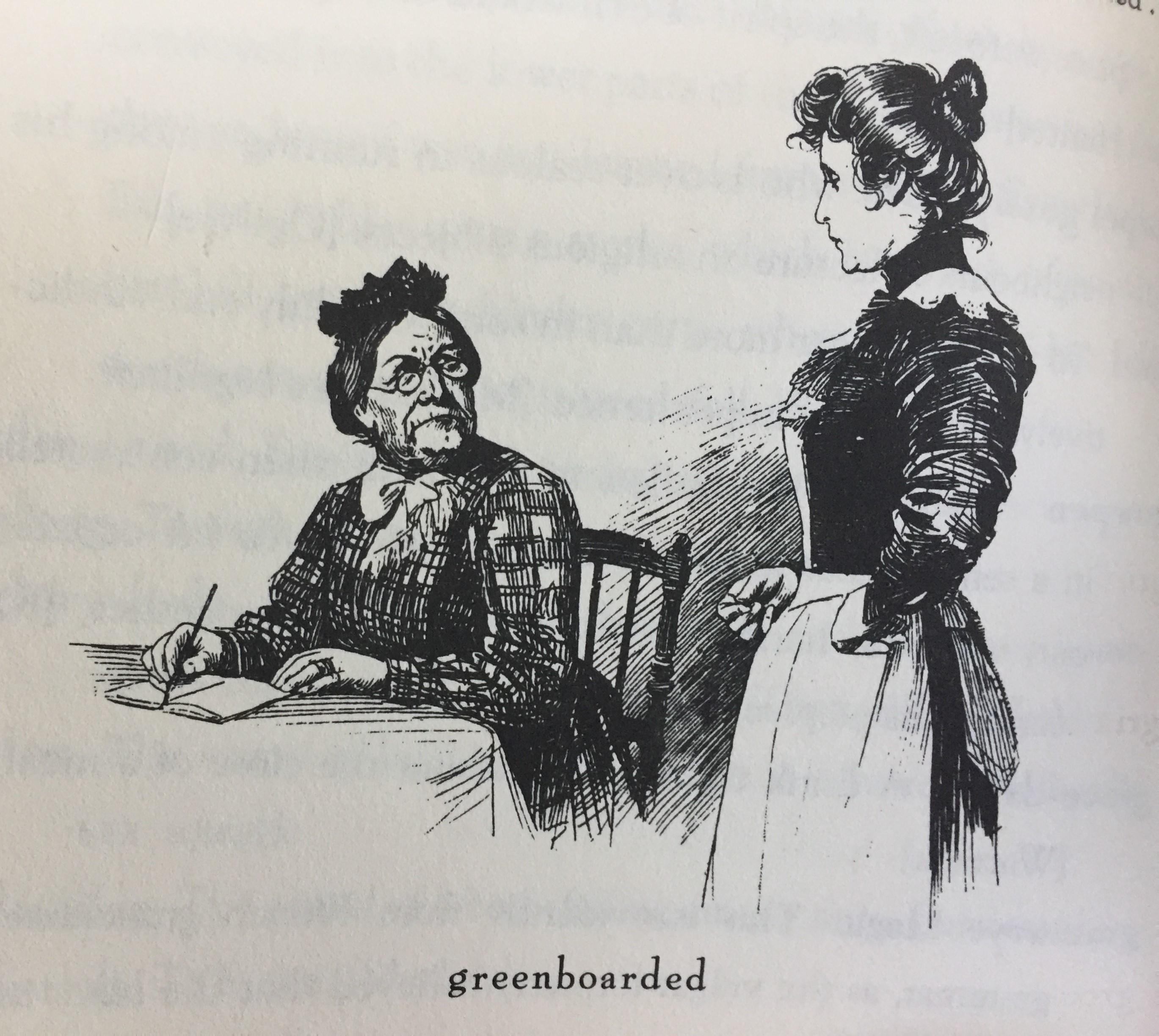

Some times, the OED selects words that I’ve never seen before and never, ever, ever want to forget. Here, for example, is one of my favorites from some time back:

Some times, the OED selects words that I’ve never seen before and never, ever, ever want to forget. Here, for example, is one of my favorites from some time back:

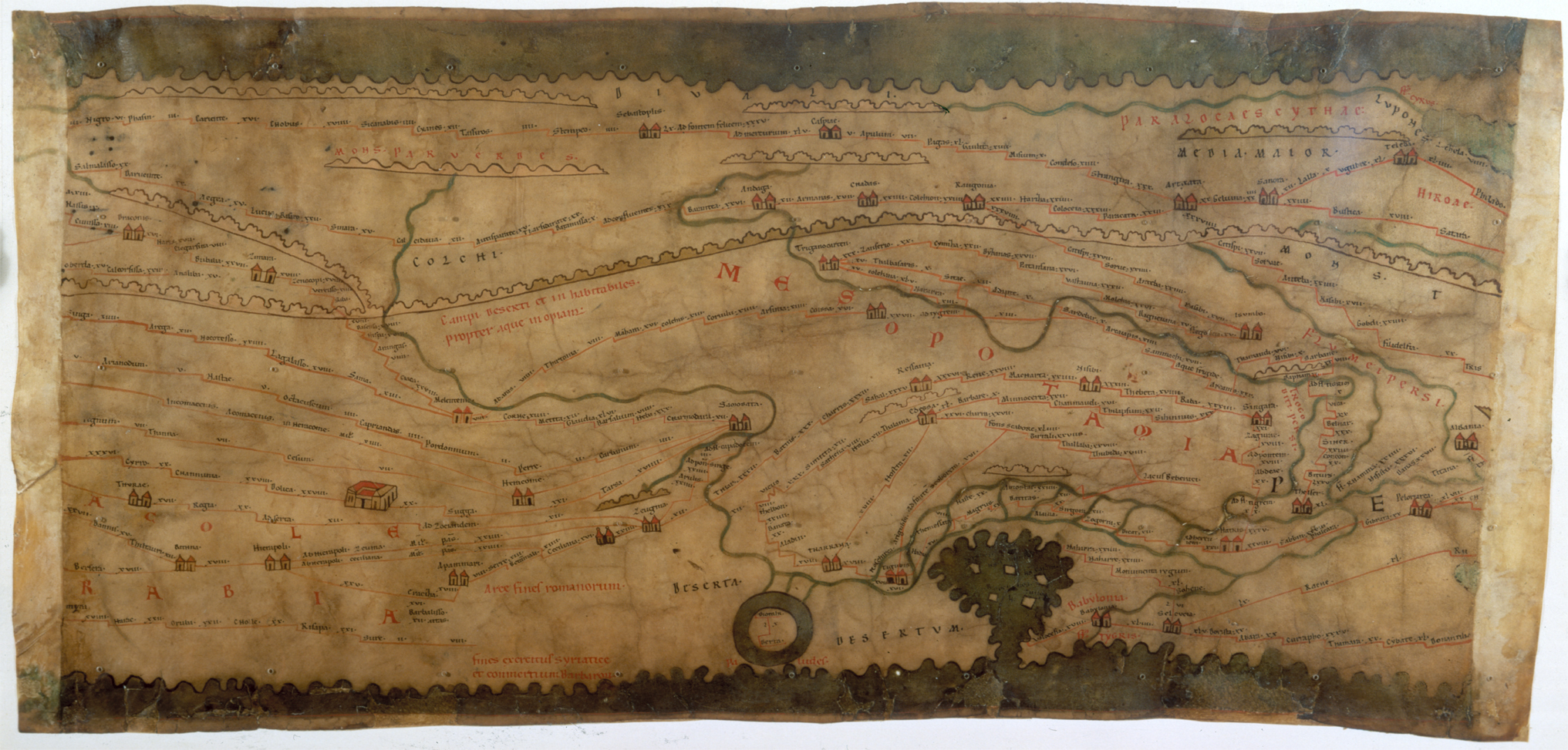

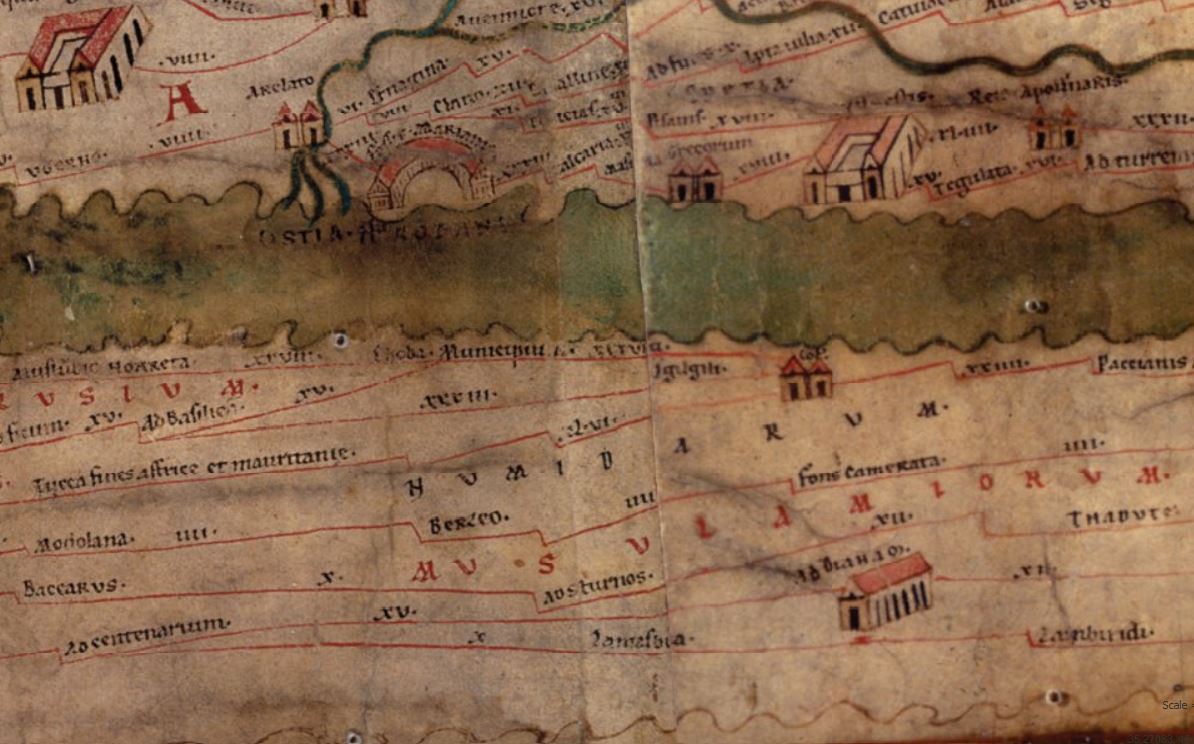

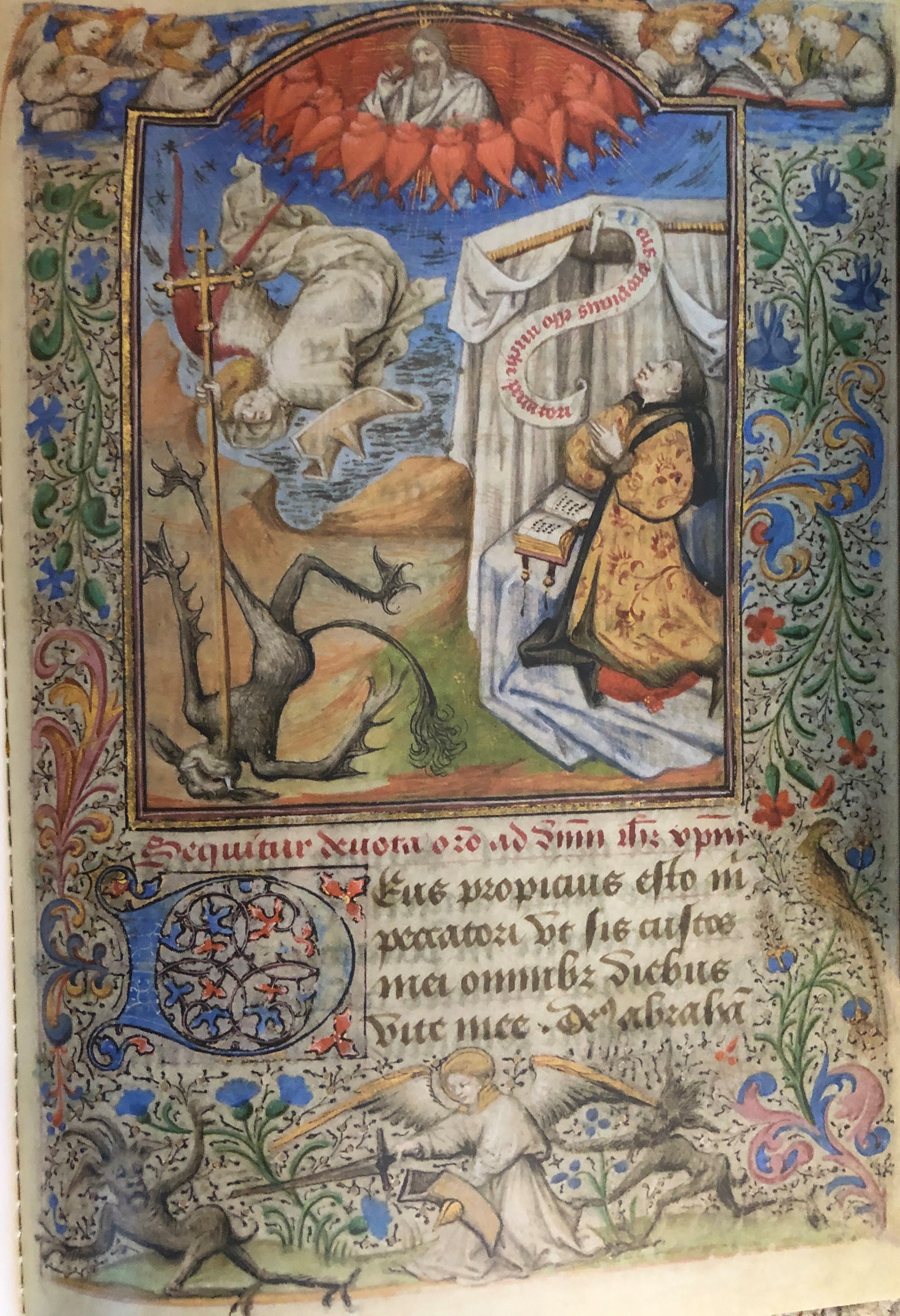

The other day as we were strolling through the magnificent passages of the medieval Nasrid palace of the Alhambra, one of my sisters said that if felt like time traveling to walk through the passages. It was like being thrown into the stories we had read as children. I understood what she meant. When strolling through a medina in Meknes several years ago, I stood and watched a storyteller weave his magic around the gathered crowd. Between the sounds, smells, responses of the crowd, the whole brought to life the opening of one of my favorite childhood stories, Eleanor Hoffman’s Mischief in Fez. It was a pleasant sort of illusion–equal parts personal nostalgia and fairy tale.

The other day as we were strolling through the magnificent passages of the medieval Nasrid palace of the Alhambra, one of my sisters said that if felt like time traveling to walk through the passages. It was like being thrown into the stories we had read as children. I understood what she meant. When strolling through a medina in Meknes several years ago, I stood and watched a storyteller weave his magic around the gathered crowd. Between the sounds, smells, responses of the crowd, the whole brought to life the opening of one of my favorite childhood stories, Eleanor Hoffman’s Mischief in Fez. It was a pleasant sort of illusion–equal parts personal nostalgia and fairy tale. If it’s true that the ceiling in that Hall was made to symbolize the seven heavens, then the placement of the throne in this room makes child’s play of the whole “divine right of kings.” For this reason, I suppose the echoes of death and power my sisters’ heard were perhaps more true than the echoes of poetry I liked to imagine in the gardens. The past of fortresses and fortifications is more truly grounded in blood and bone than anything else. If you want a sobering read of the history of the Alhambra, keep going with the aforementioned history by Irwin. It washes away some of that sepia patina of fairy tale pretty quickly.

If it’s true that the ceiling in that Hall was made to symbolize the seven heavens, then the placement of the throne in this room makes child’s play of the whole “divine right of kings.” For this reason, I suppose the echoes of death and power my sisters’ heard were perhaps more true than the echoes of poetry I liked to imagine in the gardens. The past of fortresses and fortifications is more truly grounded in blood and bone than anything else. If you want a sobering read of the history of the Alhambra, keep going with the aforementioned history by Irwin. It washes away some of that sepia patina of fairy tale pretty quickly.

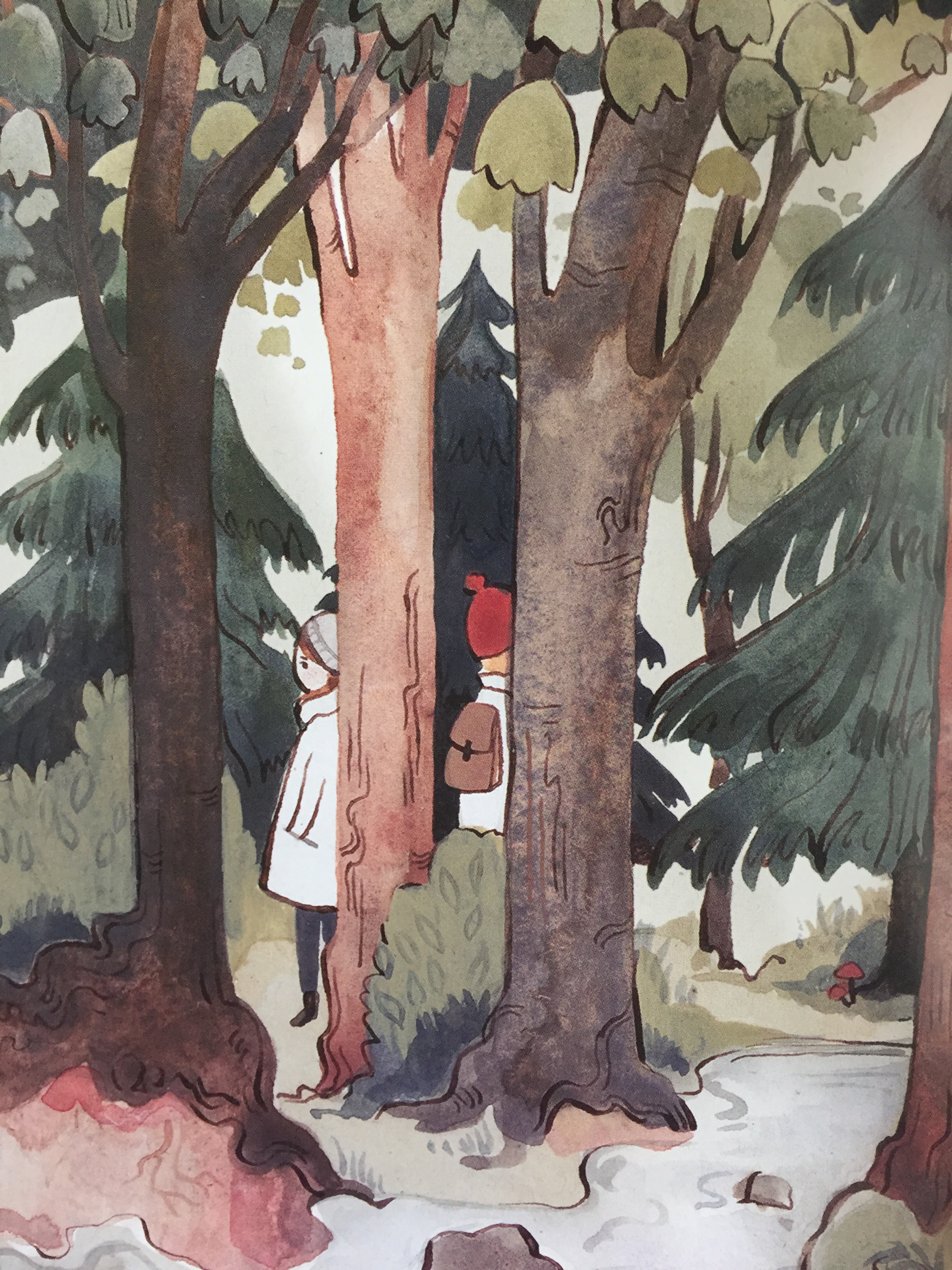

Rađljóst – an Icelandic noun meaning “enough light to find your way by” (25). I’m willing to bet that after simply reading the word, each of our imaginations conjures woods where we’d like to be at twilight, watching the shadows take on strange hues of violet and blue as night rises, and as the light dwindles to a mere ghost leading us through the trees.

Rađljóst – an Icelandic noun meaning “enough light to find your way by” (25). I’m willing to bet that after simply reading the word, each of our imaginations conjures woods where we’d like to be at twilight, watching the shadows take on strange hues of violet and blue as night rises, and as the light dwindles to a mere ghost leading us through the trees.